By: Chloe Meyer-Gehrke – 2022 Summer Intern

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, enslaved women in America chewed cotton root to induce abortions. It was a form of resistance; to give birth would be to deliver one more slave to their masters and to condemn their children to a life of slavery.

In the Middle Ages in Europe, the church exiled women for life if they received an abortion—unless the pregnancy was from a husband who has mistreated or left them, in which case their exile lasted only 10 years. The church saw abortion as a subversion of a husband’s power over his wife, the refusal to bear his children.

In the centuries before British colonization of America, Native American women knew how to use herbs like black root and cedar root to end unwanted pregnancies. This was not a moral dilemma, but a personal decision between a pregnant woman and the other female members of her tribe.

In early America, a doctor could not definitively confirm a pregnancy until “quickening,” an event in the fourth or fifth month, when the mother first felt the fetus move. Before this time, many women—often those who were unmarried, unable to support children, or afraid of the high maternal mortality rates of the time—used herbal remedies to “restore menstruation.” This was common and unremarkable; a woman’s reproductive health was a personal matter, one of her domestic responsibilities, between her and, in some cases, a midwife.

In 1969, Norma McCorvey got pregnant for a third time at age 21, a struggling waitress with a drug problem and the third consecutive woman in her family to get pregnant young and unmarried. She’d already given up her first two children for adoption, unprepared to be a responsible mother. Soon, a visit to a doctor became a visit to a lawyer, and then more lawyers, and before she knew it she was the iconic “Roe”—for Jane Roe, a pseudonym to protect her identity—of Roe v. Wade, the case that legalized abortion in America, though it was too late for her—she’d given birth while the case was in court and had given up a third child for adoption.

The modern American right would have us believe that abortion is an absolute ethical wrong, a religious sin, the hallmark of a morally bankrupt society, but the reality is nowhere near that simple. Abortion has existed in different forms for practically all of human history, and, at different times in this history and in different parts of the world, we’ve operated on radically different moral and religious systems. If a slave aborted her baby to save it from a life in slavery, was it wrong?

If a Native American woman took herbs her tribe had been using to induce abortions for centuries, was it wrong?

Banning abortion is not supported, as Supreme Court Justice Alito suggested in his recent opinion, supported by any kind of “tradition” or “history,” at least not outside of today’s conservative, Christian rhetoric. It also is not an absolute moral victory over sin and murder as “pro-life” Christians argue.

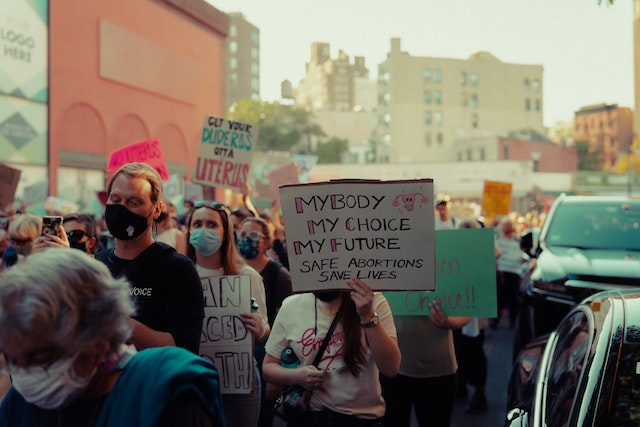

The abortion debate has lost track of reality. The moral discussions are not founded in facts and concrete truths that will support laws for all of society. There is no possible end to this debate; one side will always believe abortion is morally wrong, and the other will believe it is morally permissible; different people with different opinions that will never be compatible.

Instead, we should focus on facts. Thousands of women died from abortions the last time it was illegal in the United States. That’s a fact. Once again, abortion will become a privilege for the wealthy when it can only be accessed by traveling across state lines.

We know that legal abortions are safe—safer, even, than childbirth. These are only the facts I know. Medical professionals—the ones who should have been front and center in this debate from the beginning—can tell us more.

As much as we would like our own philosophical outlooks to be fact, they aren’t. Abortion in one context, culture, or moral system is seen as a neutral or even positive act, but seen as morally deplorable in another. These sorts of claims will always be subject to change, and relying on them over the harsh, messy realities of the world we live in and the women who seek—who need—abortions will only lead to idealized, unrealistic, and, ultimately, harmful outcomes.

We can and must prioritize living, breathing women over moral outrage and easy solutions.

Chloe Meyer-Gehrke wrote this opinion piece while interning for the World Affairs Council of Harrisburg and PA Media Group. It was published here.